How Does the Economy Affect Marriage and Family

Editor's Annotation: This research brief is an edited version of a research cursory prepared for the Opportunity America-AEI-Brookings Working-Class Grouping. Go hither to read or download the full brief.

When it comes to matrimony and family life, America is increasingly divided. College-educated and more affluent Americans enjoy relatively strong and stable marriages and the economic and social benefits that flow from such marriages. By dissimilarity, not just poor but also working-class Americans face rising rates of family instability, single parenthood, and life-long singleness. Their families are increasingly fragile and poor and working-course Americans pay a serious economic, social, and psychological price for the fragility of their families.1

The Fragility of Working-Class Marriages and Families

Before the 1970s, there were not big class divides in American family life. The vast bulk of Americans got and stayed married, and most children lived in stable, 2-parent families.2 But since the 1960s, the U.s.a. has witnessed an emerging substantial marriage split up past grade. Start, poor Americans became markedly less likely to get and stay married. Then, starting in the 1980s, working-form Americans became less probable to get and stay married.3 The current state of marriage and family life and the class divisions that mark America'southward families can be seen past looking at contemporary trends in spousal relationship, cohabitation, nonmarital childbearing, divorce, children'due south family structure, and marital quality.

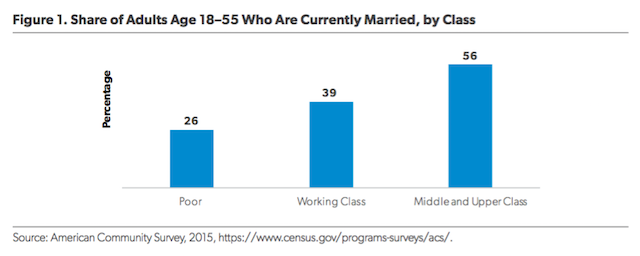

One of the most dramatic indicators of the matrimony divide in America is the share of adults age 18–55 who are married. Figure 1 indicates that a majority of centre- and upper-class Americans are married, whereas but a minority of working-class Americans are married. This stands in marked dissimilarity to the 1970s, when at that place were virtually no form divides in the share of adults married, and a majority of adults across the class spectrum were married.iv At the aforementioned time, Figure ane indicates that working-class Americans fall almost halfway between poor and middle- and upper-class Americans when it comes to the share who are married.*

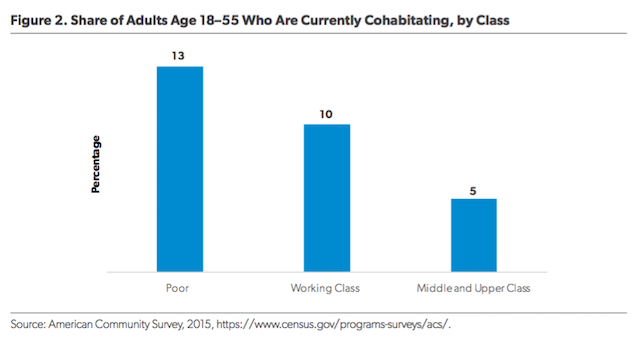

When it comes to coupling, poor and working-class Americans are more likely to substitute cohabitation for marriage. Figure 2 shows that poor Americans are most three times more than probable to cohabit, and working-class Americans are twice as likely to cohabit, compared with their middle- and upper-class peers age eighteen–55.

Taken together, these figures suggest that lower- income and less-educated Americans are more likely to be living outside of a partnership. Specifically, about six in 10 poor Americans are unmarried, almost five in x working-class Americans are unmarried, and about iv in 10 middle- and upper-class Americans are single.

Withal, when it comes to another fundamental feature of family life—childbearing—working-grade and particularly poor women are more likely to have children than their middle- and upper-course peers (see Effigy 3). Estimates derived from the 2013–fifteen National Survey of Family Growth signal that poor women currently have nearly ii.four children, compared with ane.8 children for working-class women, and i.7 children for middle- and upper-class women. Poor women, in item, starting time childbearing before and end up having markedly more than children than more affluent women.

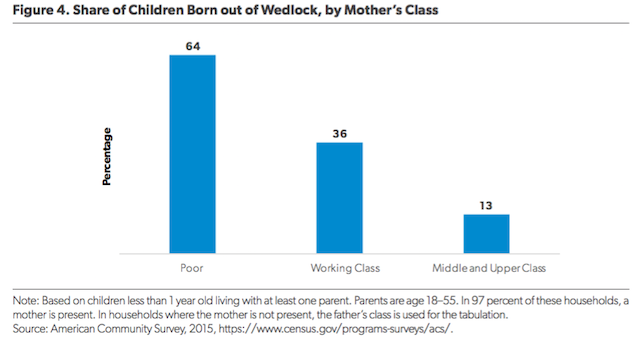

But the fact that working-course and poor Americans are less likely to exist married likewise means they are more likely to take these children outside of wedlock. In fact, equally Figure 4 indicates, children born to working-class mothers are nigh iii times every bit probable to be born outside of wedlock, compared with children born to center- and upper-class mothers. Children built-in to poor mothers are about five times as probable to be born out of wedlock.

Ii points are particularly salient here. First, nonmarital childbearing is comparatively rare among more than flush and educated women. Second, it is still the case that a majority of babies born to working-form mothers are born in wedlock. In other words, union is still connected to parenthood for most working-class parents having a baby.

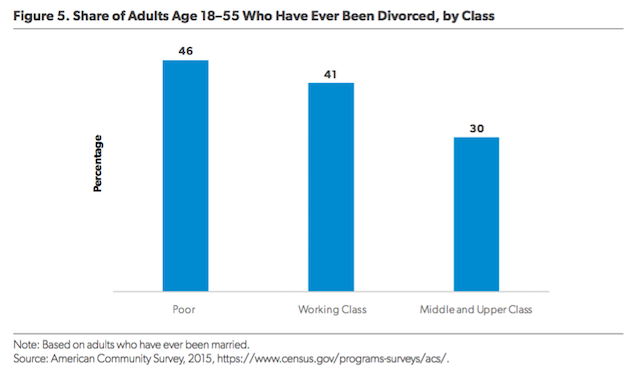

Divorce is besides more common among working-course and poor adults age 18–55, provided that they take married in the commencement identify. Figure 5 shows that less than one-third of ever-married middle- and upper-class men and women accept ever been divorced. Among working-form and poor men and women who have ever married, more than forty percent have ever been divorced.

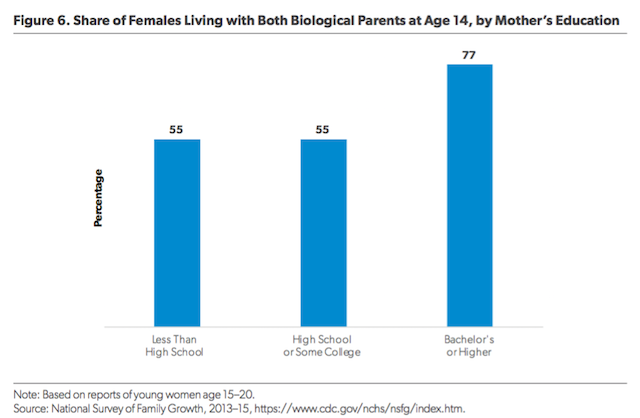

High rates of nonmarital childbearing and divorce amidst working-class and poor adults translate into more family unit instability and unmarried parenthood for children in working-class and poor communities. Figure 6 indicates the vast majority of centre- and upper-class teenage girls grew up in an intact dwelling headed past two biological parents, whereas 55 percent of working-class girls lived in such a dwelling at age xiv, as did 55 percent of poor girls.5 The bottom line: The greater fragility of union and family unit life in poor and working-form families ways that fewer children in such homes live with 2 biological parents. Children are more likely to thrive educationally, socially, and professionally when they are raised by married, biological parents, compared with beingness raised by a unmarried parent or a stepfamily.6

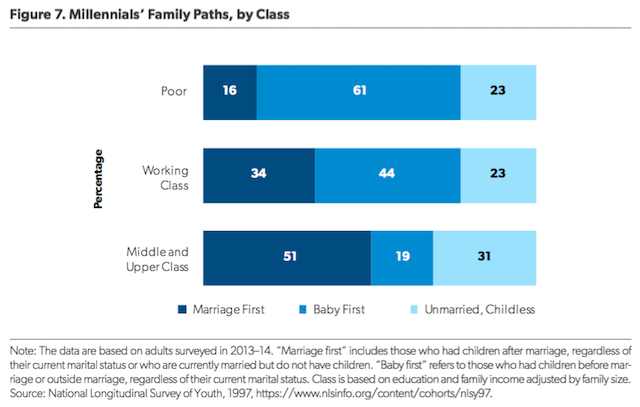

When nosotros look at trends in union and parenthood for immature adults in particular, we likewise see marked differences past course.7 Figure 7 indicates that poor and working-course millennials age 28–34 are much more than probable to have children before or outside union. In contrast, middle- and upper-class millennials are markedly more probable to marry before having any children or to accept postponed or avoided marriage and parenthood birthday. For case, 44 percent of working-class millennials take had a child before wedlock, whereas 51 percent of centre- and upper-class millennials have married beginning.

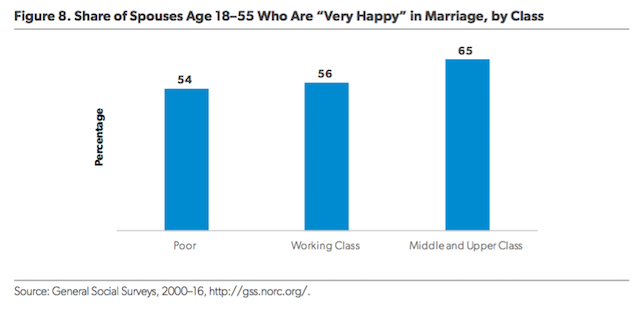

Family structure is an important predictor of the economical, social, and psychological well-existence of adults and children.viii But the relationship quality of marriages also matters, both for developed outcomes and children'southward outcomes.ix Is in that location also a class divide in marital quality? Equally Figure 8 indicates, there is indeed a difference in marital quality by class, but this difference is not as striking as most of the demographic differences previously noted. On the other hand, the share of working-class and poor Americans who are married is markedly lower, which means they are a more selective grouping.

Finally, as the figures in the appendix (encounter full report) indicate, the class divide in wedlock and family life is more marked when nosotros exclude immigrants from our analysis. For instance, the share of working-class married adults is somewhat lower, and the share of divorced adults is somewhat higher, when we exclude immigrants from our calculations. Figure A5 indicates that the share of working-form adults who are married falls from 39 percent to 35 percent when nosotros focus but on native-built-in Americans. And the share of working-class adults who are divorced rises from 41 percent to 45 percent when we focus only on native-born Americans, as illustrated by Figure A8.

In other words, the class split betwixt middle- and upper-class Americans and working-course Americans in family life would exist bigger were it non for the presence of immigrants. That is because immigrants are disproportionately likely to be married, particularly in the ranks of the working class and even more so the poor (see Figure A10). Still, the basic story this research brief tells about the differences betwixt middle- and upper-class Americans and working-form Americans remains similar when we limit our analysis to native-born Americans.

In sum, when it comes to the structure and quality of wedlock and family life, America is increasingly divided past class. Middle- and upper-class Americans are more than probable to benefit from strong and stable marriages; by comparison, working-grade and poor Americans increasingly face more fragile families. This family divide, in turn, often leaves poor and working-class men, women, and their children doubly disadvantaged: They take more fragile families and fewer socioeconomic resource.x

What Explains the Marriage Divide in America?

Given the grade divide in union and family patterns, last that this split up is driven solely past economic factors is tempting. But equally Brookings economist Isabel Sawhill has observed, a "purely economical theory falls short as an explanation of the dramatic transformation of family life in the U.S. in recent decades."11 Consider, for instance, that there was no marked increment in divorce, family unit instability, or single parenthood at the height of the Great Low in the 1930s. A different policy, cultural, and civic context in that era meant that economic distress did not automatically lead to greater family instability.

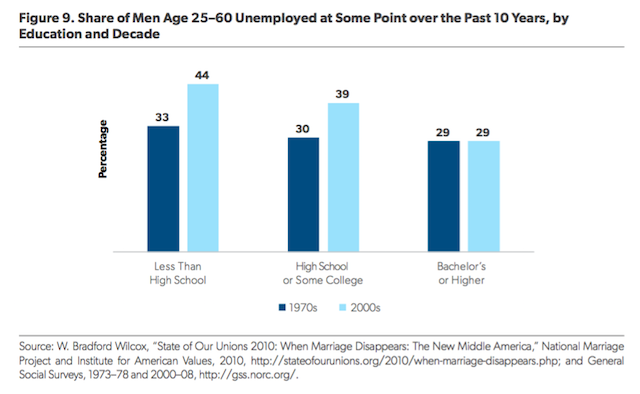

By contrast, a series of interlocking economic, policy, civic, and cultural changes since the 1960s in America combined to create a perfect family storm for poor and working-class Americans.12 On the economical front, the move to a postindustrial economy in the 1970s fabricated it more hard for poor and working-class men to discover and agree stable, decent-paying jobs.13 See, for example, the increase in unemployment for less-educated but non college-educated men depicted in Effigy 9.14 The losses that less-educated men have experienced since the 1970s in job stability and existent income have rendered them less "marriageable," that is, less attractive as husbands—and more vulnerable to divorce.fifteen

But it is not only economics. For example, Cornell sociologist Daniel Lichter and colleagues have looked carefully at economical and family change in the 1980s and 1990s; they found that changes in land and national economic factors did play a role in fueling the retreat from marriage in this period.16 They note, however, that shifts in country-level employment trends and macroeconomic performance practice not explicate the majority of the decline of marriage in this period; indeed, the retreat from matrimony continued in the 1990s fifty-fifty every bit the economic system boomed across much of the state in this decade. In their words: "Our results call into question the appropriateness of monocausal economic explanations of failing matrimony."17

The refuse of marriage and rising of single parenthood in the late 1960s preceded the economic changes that undercut men's wages and job stability in the 1970s.18 Shifts in the culture weakened marriage before shifts in the economy directly afflicted working-form families. The counterculture, sexual revolution, and ascension of expressive individualism in the 1960s and 1970s undercut the norms, values, and virtues that sustain potent and stable marriages and families. In other words, marriage-related civilisation shifted earlier the economic changes that oftentimes garner more attention.19

Only why would these cultural changes disparately affect poor and working-class Americans? These shifts ended up disparately affecting poor and so working-class men, women, and their children for three reasons.

First, because working-class and poor Americans take less of a social and economic stake in stable marriage, they depend more on cultural supports for marriage than practice their heart- and upper-class peers.xx For case, middle- and upper-class Americans are more likely to own a habitation, and home ownership stabilizes union apart from whether homeowners accept a potent normative commitment to marital permanence.21 Past dissimilarity, when marriage norms get weaker, working-class and poor couples—who are much less likely to own a home together—accept fewer reasons to avoid divorce. So, the reject in normative support for matrimony has afflicted working-class couples more than because they have a smaller economical pale in marriage and accept depended more than on marriage-related norms to become and stay married.

Second, working-class and poor Americans have fewer cultural and educational resources to successfully navigate the increasingly deinstitutionalized grapheme of dating, childbearing, and wedlock. The legal scholar Amy Wax argues that the "moral deregulation" of matters related to sex, parenthood, marriage, and divorce proved more than difficult for poor and working-class Americans to navigate than for more educated and affluent Americans because the latter group was and remains more than probable to approach these matters with a disciplined, long-term perspective.22 By contrast, poor and working-grade Americans were more probable to take a short-term view of these matters and make decisions that were gratifying in the short term merely hurt their long-term well-beingness, or that of their children and families.

Sociologists Sharon Sassler and Amanda Miller interpret this dynamic somewhat differently: They contend that the stresses facing poor and working-form young adults leave them with a macerated sense of efficacy, which in plow makes it more than hard for them to navigate today'south choices related to sex, contraception, childbearing, and marriage than their amend-educated and more than affluent peers.23 But the lesser line is similar: Today's ethos of freedom and choice when it comes to dating, childbearing, and marriage is more hard for working-class and poor Americans to navigate. For example, immature adults from less-educated homes are less probable to consistently apply contraception than are immature adults from more educated homes, as Effigy x indicates.

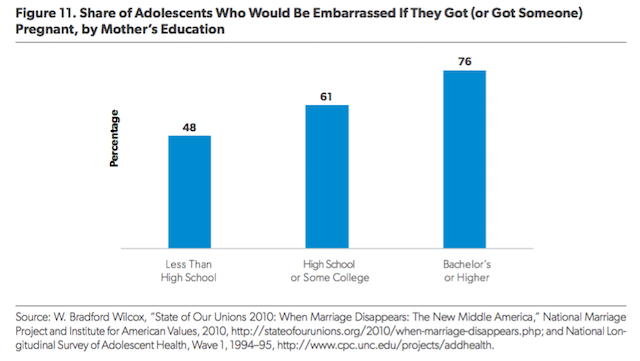

Third, in recent years, middle- and upper-class Americans have rejected the most permissive dimensions of the counterculture for themselves and their children, even as poor and working-class Americans have adapted a more permissive orientation toward matters such equally divorce and premarital sex activity.24 The stop result has been that cardinal norms, values, and virtues—from fidelity to attitudes about teen pregnancy—that sustain a potent matrimony culture are now generally weaker in poor and working-class communities.25

Figure 11 is illustrative, for instance, of the ways in which norms against teenage childbearing are weaker in poor and working-class communities than they are in center- and upper-class communities. It shows that adolescents from more educated and affluent homes are more probable to written report they would be embarrassed by a teenage pregnancy than are their peers from less-educated homes. This figure is indicative of the ways in which class norms, ideals, and expectations are more marriage-friendly in the middle and upper class.

Moreover, these cultural differences seem to thing in structuring electric current patterns of family unit formation. One analysis of nonmarital childbearing found that family income growing up explained about 15 percent of the deviation in nonmarital childbearing between immature women from college-educated homes and those from less-educated homes, whereas cultural factors—for instance, an boyish woman's orientation toward college, her history of sex activity, and her attitudes to single parenthood—deemed for about xx percent of the class difference in nonmarital childbearing.26 At least for this family outcome, and so, economic science and culture both appear to be important in explaining the class divide in nonmarital childbearing. Moreover, these economic and cultural dynamics reinforce 1 another in different, grade-based social networks amidst today's young adults.

Starting in the 1960s, the policy context too changed in means that take undercut marriage and stable family life, specially in poor and working-class communities. Authorizing no-error divorce, eliminating human-in-the-house rules, and passing more generous welfare programs in the 1960s and 1970s all weakened the legal and economic importance of spousal relationship and two-parent families.27 Poor and working-class families were and continue today to exist affected more by these changes because they have more contact with the land for material back up and assistance. Now, considering many means-tested programs have expanded, more than 40 percentage of families with children receive support from at to the lowest degree i transfer program—such as Medicaid, food stamps, and Pell Grants; many of these programs penalize wedlock.28

Such penalties may currently play a small role in discouraging marriage among poor and working-class couples.29 In fact, i national survey establish that 31 percent of Americans say they personally know someone who chose not to marry for fear of losing a ways-tested benefit.30 More than broadly, shifts in family law and the expansion of the welfare state since the 1960s seem to have played a modest role in undercutting wedlock among the poor starting in the late 1960s. In more than recent decades, public policies may now be undercutting spousal relationship amongst working-form families, insofar every bit marriage penalties related to programs such equally Medicaid and food stamps are now more than likely to affect working-form families than poor families.31

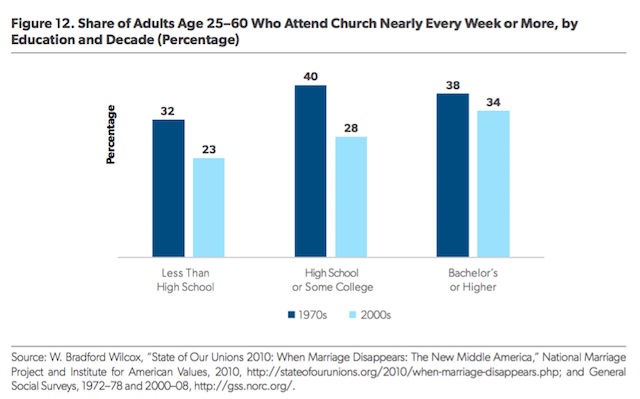

Finally, the civic fabric of America has frayed since the 1960s in means that have disparately affected poor and working-class Americans—and their families. Membership and involvement in secular and religious organizations have declined across the board, but they have fallen more precipitously among poor and working-class Americans.32 This matters because such organizations have tended to support families over the years. This is particularly true for religious institutions, which often offer psychic, social, and moral support to marriage and family life. Indeed, Americans who regularly attend religious service are more likely to marry, accept children in wedlock, avoid divorce, and savour higher-quality relationships.33 Nevertheless, as Effigy 12 indicates, religious attendance has fallen most amidst Americans with less education.

Moreover, many of these religious institutions have been less likely to clearly and regularly accost bug related to marriage and family life since the 1970s. Considering of demographic changes in the pews and changes in the broader civilization and the churches, pastors, priests, and lay leaders have get more reluctant to address topics related to sex, marriage, divorce, and nonmarital childbearing.34 This means that all Americans, including working-class men and women, are less likely to receive direction and guidance almost union and family life that might otherwise strengthen and stabilize their families.

In sum, the nation'south marriage divide is rooted in economical, cultural, policy, and borough changes that all undercut the normative, fiscal, and communal bases of strong and stable marriages and families in poor and working-form communities beyond America.

Determination

This Opportunity America–AEI–Brookings research brief documents major differences in marriage and family life between working-class and middle- and upper-class Americans. Moreover, the roots of the union divide between the middle and upper class and the working class in America are conspicuously varied. No single panacea volition bridge this carve up. Policymakers, business leaders, and educators need to pursue a range of educational and work-related policies to shore up the economic foundations of working-class and poor families. They also need to eliminate or minimize the marriage penalties embedded in many of our means-tested policies. And the country'due south secular and religious borough leaders should exercise more to engage and involve working-class and poor Americans—particularly poor and working-grade men who tend to have the weakest ties to our civic institutions.

Finally, leaders need to pursue a strategy to extend norms around wedlock and childbearing—which remain stiff amid the center and upper class—to working-form and poor women and men. The culling to taking steps like these is to have a globe where eye- and upper-grade Americans benefit from strong, stable families while anybody else faces increasingly fragile families, and where high rates of economic inequality and kid poverty are locked in by a marriage divide that puts working-class and poor Americans—and their children—at a stark disadvantage.

Due west. Bradford Wilcox is a senior boyfriend at the Institute for Family unit Studies, a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and the manager of the National Marriage Projection at the University of Virginia. Wendy Wang is director of research at the Institute for Family Studies and a old senior researcher at Pew Enquiry Center.

*In Figures 1 through 8, "working class" generally refers to adults whose (adapted) family income is between the 20th and the 50th income percentiles and who have a high school degree or some college education but practice non have a bachelor'due south caste. Currently, this covers about 21 percentage of the developed population age 18–55. "Poor" refers to men and women whose (adjusted) family unit income is below the 20th percentile or who are high school drop-outs. This covers about 22 per centum of the developed population age xviii–55. "Eye and upper grade" refers to men and women who have a college degree or whose (adjusted) income is greater than the 50th percentile. This includes about 57 per centum of the adult population age xviii–55. Income is adjusted for family unit size.

1. David Autor and Melanie Wasserman, "Wayward Sons: The Emerging Gender Gap in Education and Labor Markets," 3rd Mode, 2013, https://economics.mit.edu/ les/8754; Kathryn Edin and Maria Kefalas, Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Maternity Before Marriage (Berkeley, CA: University of California Printing, 2011); Sara McLanahan, "Diverging Destinies: How Children Are Faring Nether the Second Demographic Transition," Census 41 (2004): 607–27, https://world wide web.jstor.org/stable/1515222?seq=1#page_scan_ tab_contents; and W. Bradford Wilcox, "State of Our Unions 2010: When Marriage Disappears: The New Middle America," National Marriage Projection and Establish for American Values, 2010, http://nationalmarriageproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Union_ 11_12_10.pdf.

2. David Ellwood and Christopher Jencks, "The Spread of Unmarried-Parent Families in the United States Since 1960," in Time to come of the Family unit, ed. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Timothy Smeeding, and Lee Rainwater (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2006).

3. Ibid; and Wilcox, "Country of Our Unions 2010."

four. Wilcox, "State of Our Unions 2010."

5. Considering of information limitations, Effigy 6 is based only on maternal teaching, not family income.

half dozen. Autor and Wasserman, "Wayward Sons"; Sara McLanahan and Gary Sandefur, Growing Up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps (Cambridge: Harvard Academy Press, 1994); and Sara McLanahan and Isabel Sawhill, "Marriage and Child Wellbeing Revisited: Introducing the Issue," Future of Children 25, no. 2 (2015): 3–ix, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43581969?seq=1#page_scan_ tab_contents.

7. Wendy Wang and W. Bradford Wilcox, "The Millennial Success Sequence: Wedlock, Kids, and the 'Success Sequence' Among Young Adults," American Enterprise Constitute and Institute for Family unit Studies, 2017, http://www.aei.org/publication/millennials-and-the-success-sequence-how-do-teaching-work-and-marriage-affect-poverty-and-fiscal-success-amongst-millennials/.

8. McLanahan and Sawhill, "Marriage and Child Wellbeing Revisited"; and W. Bradford Wilcox et al., Why Union Matters: 30 Conclusions from the Social Sciences (New York: Found for American Values and National Marriage Project, 2011).

nine. Susan L. Brown, "Matrimony and Child Well-Being: Research and Policy Perspectives," Periodical of Marriage and Family 72 (2010): 1059–77, https://world wide web.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3091824/; Christine M. Proulx, Heather Helms, and Cheryl Buehler, "Marital Quality and Personal Well-Being: A Meta-Assay," Journal of Marriage and Family Life 69 (2007): 576–93, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00393.x/abstract; and Wilcox et al., Why Union Matters.

10. McLanahan, "Diverging Destinies."

xi. Isabel Sawhill, "The Economics of Marriage, and Family Breakup," Brookings Establishment, 2014, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/the-economic science-of-matrimony-and-family-breakup/.

12. Ellwood and Jencks, "The Spread of Single-Parent Families in the Usa Since 1960"; and Wilcox, "State of Our Unions 2010."

xiii. Andrew J. Cherlin, The Spousal relationship-Become-Round: The Land of Marriage and the Family unit in America Today (New York: Vintage, 2009); and William Julius Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

xiv. Figures 9 through 12 are based on education alone; they do non contain data regarding household income.

fifteen. Autor and Wasserman, "Wayward Sons."

16. Daniel Lichter, Diane Thou. McLaughlin, and David C. Ribar, "Economic Restructuring and the Retreat from Marriage," Social Science Research 31 (2002): 230–56, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/commodity/pii/S0049089X01907288.

17. Ibid.

18. Andrew J. Cherlin, Labor'south Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of Working-Grade Family in America (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2014).

19. Cherlin, The Spousal relationship-Become-Round.

twenty. W. Bradford Wilcox, Nicholas Wolfinger, and Charles Stokes, "1 Nation, Divided: Culture, Borough Institutions, and the Marriage Carve up," Future of Children 25 (2015): 111–27, https://www.princeton.edu/futureofchildren/publications/docs/marriagedivide.pdf.

21. Scott J. South and Glenna Spitze, "Determinants of Divorce over the Marital Life Course," American Sociological Review 51 (1986): 583–xc, https://world wide web.jstor.org/stable/2095590?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

22. Amy Wax, "Diverging Family Structure and 'Rational' Beliefs: The Decline in Marriage every bit a Disorder of Choice," in Research Handbook on the Economics of Family Law, ed. Lloyd R. Cohen and Joshua D. Wright (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2011), 15–71.

23. Sharon Sassler and Amanda Miller, Cohabitation Nation: Gender, Class, and the Remaking of Relationships (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017).

24. Wilcox, "State of Our Unions 2010."

25. Ibid.

26. Wilcox, Wolfinger, and Stokes, "One Nation, Divided."

27. Ibid.

28. W. Bradford Wilcox, Joseph P. Price, and Angela Rachidi, "Marriage, Penalized: Does Social-Welfare Policy Touch Family Formation?," American Enterprise Constitute and Institute for Family Studies, 2016, http://world wide web.aei.org/publication/spousal relationship-penalized-does-social-welfare-policy-affect-family-formation/.

29. Douglas Besharov and Neil Gilbert, "Marriage Penalties in the Mod Welfare State," RStreet Institute, 2015, http://www.rstreet.org/policy-written report/matrimony-penalties-in-the-modern-social-welfare-state/; and Wilcox, Toll, and Rachidi, "Union, Penalized."

30. Wilcox, Price, and Rachidi, "Marriage,Penalized."

31. Ibid.

32. Robert D. Putnam, Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015); and Wilcox, "State of Our Unions 2010."

33. West. Bradford Wilcox and Nicholas Wolfinger, Soul Mates: Organized religion, Sexual practice, Honey, and Matrimony Among African Americans and Latinos (New York: Oxford Academy Printing, 2016).

34. W. Bradford Wilcox, Soft Patriarchs, New Men: How Christianity Shapes Fathers and Husbands (Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press, 2004); Wilcox and Wolfinger, Soul Mates.

Source: https://ifstudies.org/blog/the-marriage-divide-how-and-why-working-class-families-are-more-fragile-today

0 Response to "How Does the Economy Affect Marriage and Family"

Publicar un comentario